March 27, 2017

Primary Research: Thomas Thwaites Talk

We invited final year GMD student Richard Underwood to respond to a lecture by Thomas Thwaites in January, part of the Design School Lecture Programme.

‘I first encountered Thomas Thwaites when I came across his toaster in the V&A. As an object it immediately caught my attention and as a story I was captivated. Over the next few weeks I kept thinking about it in reference to my own practice as a maker and was delighted when I found out that it was the same designer who was giving this lecture. Thomas Thwaites is a designer who uses technology and science to speculate about how the future could be and also what the present might look like from various different viewpoints. His research is often at the forefront of his work, using his design journey as a vehicle for storytelling. He spoke to us about a few of his projects;

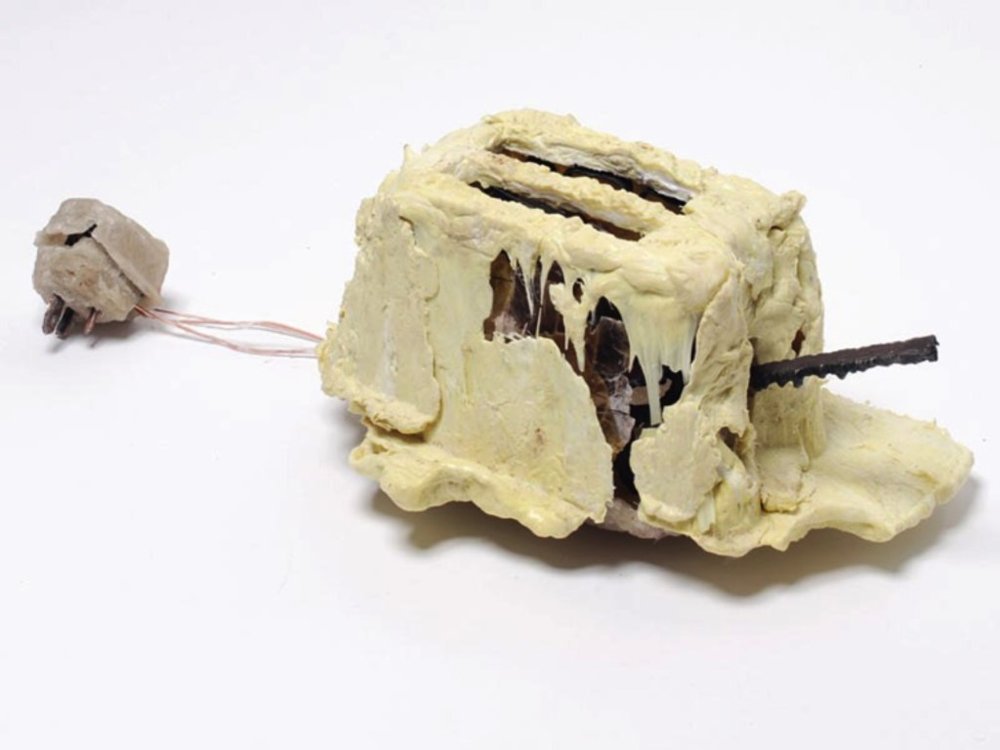

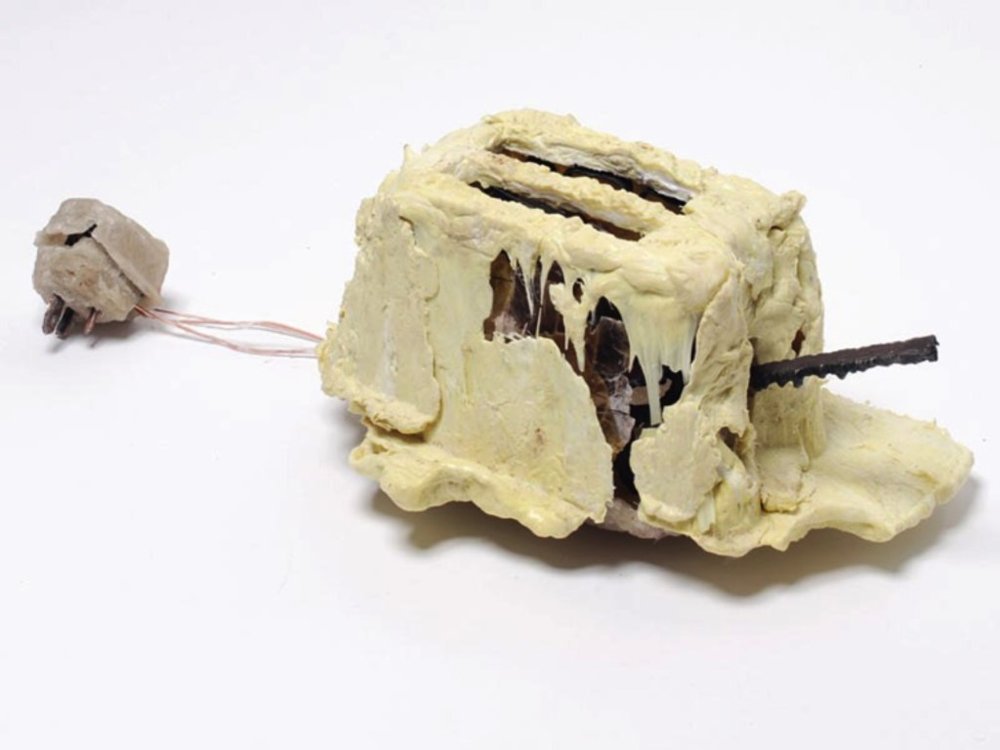

Toaster Project

Although in his work Thomas would often make things, he felt that he was always taking things that were already made and putting them together. He decided to try to make a toaster, inspired by a quote from Douglas Adams, “left to his own devices he couldn’t build a toaster. He could just about make a sandwich and that was it.” He bought a toaster for under £4 and took it apart to discover around 400 parts made from over 100 different materials. Not to be put off, he reduced this to four main components: steel, mica, plastic, copper. The project took him to mines in Wales and Scotland to gather ore and come up with ingenious ways of extracting the materials. It seems that at nearly every step of the way he had to “cheat” or make concessions to his initial brief, but he eventually created a toaster that worked for a few seconds before melting itself.

This project in particular has inspired me in two main ways. Firstly, it has really shown me that the outcome of a project is not necessarily the only vehicle for telling a story. The journey of that process, when researched thoroughly and documented meticulously, can make us see the system in which we live in a new light. In this case the struggle to create such a common, cheap object shows us not only the bizarre economies of scale at play in global capitalism, but also how we are held and supported through every action we take by the past and present of human society. Every concession Thwaites had to make is a testament to this rather than a display of failure.

Goatman… Or a holiday from being human

(Image source: Tim Bowditch from thomasthwaites.com)

During a particular period of existential crisis, Thomas felt jealous of animals’ ability to be present. Rather than turning to mindfulness, he wondered whether he could use technology to take on the characteristics of an animal and connect to that feeling by living in their shoes (figuratively and literally). An application to the Wellcome Trust secured him the funding to do just that.

Drawing on a range of experts including a shaman, neuroscientists, biologists, prosthetists and animal behaviourists, his journey eventually took him to the Alps to live with a herd of goats for three days – walking on all fours using custom prosthetics, eating grass and sleeping outside.

This particular project won him an Ig Nobel prize which is for achievements which first make people laugh and then make them think. This captures exactly what is so refreshing about Thomas Thwaites’ work. Although he regularly calls into question many fundamental aspects of our society, he does so in such a humorous and personal way it never feels preachy. I should not imply that his work is only critical. It also displays a love of and interest in the world and how it works. This is the place that any questioning and criticism comes from and encourages a wide and diverse audience to participate in that discussion.

Living History

Drawing inspiration on the magical, grainy footage of early cinema, Thomas imagines whether our early attempts at virtual reality might carry the same romance to people of the future. Details about our time have been lost and facts are mixed together haphazardly with exaggeration and guesswork. He showed us a clip in which the narrator attempted to explain the phenomenon of cars:

“These lethal machines were found in even the farthest reaches of the civilisation. The status of a vehicle’s occupant was indicated through a complex interplay of external signals. The most prominent of these signals was the overall colour of the vehicle. Gold vehicles were rare and highly prized, reserved for higher status individuals whereas white, red and black vehicles were common and clearly of lower status.”

The use of virtual reality technology combined with otherwise mostly mundane footage provides an interesting juxtaposition that brings a new awareness to even our most everyday actions. The authoritative narrator constantly makes us question how these actions may be perceived in a different context. The relaxed humour makes this a joy to experience even though some of the commentary is quite scathing.’

Richard Underwood GMD Year 3